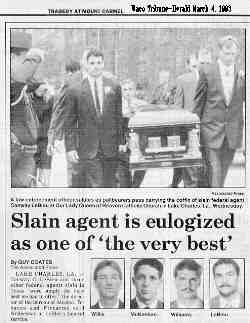

The ATF agent deaths were necessary to justify a military siege and testing of the National Response Plan. Armed with headlines (like this one in the Waco Tribune-Herald, March 4, 1993), the US military had all the public approval it needed to escalate the war against the Branch Davidians. Compare the tactics in Waco to those in the infamous Gulf of Tonkin incident, described below. |

Few military operations are designed for failure. But the February 28, 1993 assault on the Mt. Carmel Center seems to have been one such operation.

Given the desire of the new military to establish new paradigms, there is reason for the failure of the raid. Without the death of the four ATF agents in the failed raid, it is doubtful that the American public would have supported moving in massive war equipment and escalating the war against the Davidians during the next 51 days. Without the deaths of the four ATF agents in the failed raid, the new paradigm of the military annihilation of citizens under the color of law would not have been established.

The Commander-in-Chief himself validated this observation: "The first thing I did after the ATF agents were killed, once we knew that the FBI was going to go in, was to ask that the military be consulted because of the quasi-military nature of the conflict, given the resources that Koresh had in his compound and their obvious willingness to use them," President Clinton said (The Washington Times, April 24, 1993).

Gulf of Tonkin Incident

The Gulf of Tonkin is a body of water off the shore of North Vietnam.

Modern history furnishes other examples of incidents deliberately set up to achieve a political result. The Pentagon Papers disclose that for six months before the Tonkin Gulf incident in August 1964, the US had been mounting clandestine military attacks against North Vietnam, including kidnapping North Vietnam citizens for intelligence information, commando raids to blow up rail and highway bridges, and bombardment of North Vietnamese coastal installations by PT boats. (Pentagon Papers, pg. 238). That was done while planning to obtain a Congressional resolution that the Administration considered equivalent to a declaration of war. (Pentagon Papers, pg. 234.)

On August 5, 1964, President Johnson called congressional leaders to the White House and told them that North Vietnamese naval vessels had flagrantly and without provocation attacked two US destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin. President Johnson had the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution drawn up, and it flew through both the House of Representatives and the Senate with virtually no debate. On August 7, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution had been passed, continuation and escalation of military reprisals against the North were given congressional blessing. "In the heat of the Tonkin clash, the Administration had accomplished … preparing the American public for escalation" (Pentagon Papers, pg. 269).

"The Tonkin Gulf reprisal constituted an important firebreak and the Tonkin Gulf resolution set US public support for virtually any action" (study quoted in Pentagon Papers, pg. 269).

Several years later the Senate Foreign Relations Committee conducted an inquiry into the events of August 1964. Senator Fulbright would later write that the Pentagon had misrepresented the actual event, and that the US had provoked the attack.

"Only when we began those later hearings on the Tonkin Gulf did it really begin to dawn on me that we had been deceived. In the beginning — before Vietnam, that is — it never occurred to me that presidents and their secretaries of state and defense would deceive a Senate committee.

"I thought you could trust them to tell you the truth, even if they did not tell you everything. But I was naive, and the misrepresentation of the Tonkin Golf affair was very effective in deceiving the Foreign Relations Committee and the country, and me, because we didn't believe it possible that we could be so completely misled." (J. William Fulbright, The Price of Empire, pg. 107.)

The Secret Raid that Lacked Only a Marching Band

With the historical perspective of the phony Gulf of Tonkin incident, let's have another look at the inept, suicidal raid plan allegedly designed by the ATF and supported by the Special Forces with "training."

According to the Treasury Report, the ATF had gathered evidence that:

- The Mt. Carmel Center was a fortress-like compound. (pg. 9)

- David Koresh had a formidable arsenal of firearms, including many illegal machine guns and unlawful destructive devices. (pg. 8).

- David Koresh posted guards at Mt. Carmel (pg. 8)

- David Koresh trained his followers to fire weapons (pg. 8).

- David Koresh believed he would have a violent confrontation with law enforcement (pg. 8)

- David Koresh was prepared to use the arsenal he was amassing (pg. 8).

- The people who lived at Mt. Carmel were "fiercely loyal" to Koresh (pg. 38).

- Of these 75 "fiercely loyal" people, large numbers were women and children. (pg. 38.)

For the raid to fail convincingly, at least two sets of people had to be fooled in different ways. The Davidians had to be fooled into thinking they were fighting off a genuine attack, and the US public, in front of their televisions, had to be fooled into thinking the raid was planned with sincere intent.

Therefore, the Davidians had to be covertly tipped off about the impending "raid," so they could make full preparations. Every effort, short of a certified letter, was made to alert the Davidians to the impending attack, and each tip was made to look like a little snafu that could happen by the operation of Murphy's law.

- Several months before the raid, the ATF rented the house across the street from the Davidians and filled it with undercover agents posing as students. The "students" were old, and drove late model, mid-sized cars similar to those driven by undercover agents and plainclothes police. Predictably, David Koresh and the Branch Davidians had become suspicious of the occupants in the undercover house.

- David Koresh told the ATF undercover agents that he had been watching the "undercover house" with binoculars (Treasury Report, pg. 54). David Koresh knew he was under suspicion and surveillance.

- Through multiple leaky channels, the ATF tipped off the local press to the impending raid several days in advance (Treasury Report, pg. 70). Such was the media furor that on the morning of the raid, five media vans were either stationed at or driving around the roads near Mt. Carmel (Treasury Report, pg. 84).

- The ATF reserved 153 rooms at three local hotels for the evening of 28 February, an action that might cause public notice and comment (Treasury Report, pg. 79).

-

On the morning of February 28, the ATF traveled from the military encampment at

Ft. Hood in a huge caravan. The Treasury Report says:

"… at Ft. Hood, the 76 agents assigned to the cattle trailers assembled at 5:00 a.m. They traveled to the staging area, the Bellmead Civic Center, in an approximately 80-vehicle convoy with a cattle trailer at each end. Many of the vehicles bore the telltale signs of government vehicles — four-door, late-model, American-made vehicles with extra antennas. All the vehicles had their headlights on. Agents report that, once underway, the convoy stretched at least a mile." (Treasury Report, pg. 81.)

"An ATF agent wearing an ATF raid jacket and local police were in the street in front of the civic center directing the convoy into the parking lot. While waiting to be briefed, some of the agents went inside the center to have coffee and doughnuts; others milled about outside. A supervisor become concerned about the visibility of the agents, many of whom wore ATF insignia or were otherwise unmistakably law enforcement personnel. He ordered everyone to go inside and remain in the civic center." (Treasury Report, pgs. 81-82).

- The ATF planned to conduct the "secret" raid in broad daylight, at 10:00 am. The ATF had to know that the Branch Davidians could see out for miles over the prairies, and given the Davidians' alleged proclivity for lookout towers and guards, had to be able to see them coming: The almost treeless terrain of the Mt. Carmel Center provided the ATF with little cover.

- The ATF arrived at the Mt. Carmel Center in noisy cattle cars. The noisy cattle cars had to go across a pothole-scarred gravel road outside the Center. The condition of the road would have amplified the noise of the cattle cars.

That's Not Murphy's Law

With this perspective on the purpose of the raid, we will examine whether the Davidians rose to the bait in Who Struck John?

But other details should be mentioned first:

We are asked to believe another manifestation of Murphy's law. The Treasury Report tells us that early on the morning of February 28, local Waco TV station KWTX cameraman Jim Peeler, on his way to cover the event, "became lost" on "back roads." There he coincidentally met a letter carrier who, coincidentally, was a Branch Davidian. Mr. Peeler asked directions and coincidentally mentioned the impending raid; naturally, the letter carrier, Davidian David Jones, went to the Mt. Carmel Center and told David Koresh about upcoming events (Treasury Report, pg. 85).

We have been asked to believe a lot, but this is beyond the pale: The location where Mr. Peeler became "lost" was within sight of the Mt. Carmel Center!

That encounter on the "back roads" was witnessed by one of the ATF undercover agents in casual clothes, accompanied by the "forward observers … in ATF battle dress utilities" and "their arrest support teams," who, we are asked to believe, were coincidentally on their way to a hay barn behind the Mt. Carmel Center (pg. 88).

The Treasury Report expresses no curiosity about how a local news reporter, covering an important local news story at a well-known local landmark, could become "lost" within eyesight of his destination.

The narration of this incident and speculations on its effect are spread over seven pages in the Treasury Report (pgs. 82 to 88), including a map and schedule of which reporter was where when, and what car he was driving. The drafters of that report worked very hard to convince the readers of the incident.

The number of pages in the Treasury Report consumed in narrating all the dumb moves of government planners and agents in the planning and execution of this investigation overstates the case. Government bureaus are notoriously reluctant to admit to their errors. The Treasury Report, however, is replete with confessions.

The Final Tip

We have already seen that the ATF deployed very obvious undercover agents across the street from the Mt. Carmel Center and that David Koresh had told them that he was watching them with binoculars.

One of these agents, Robert Rodriguez, had been taking Bible lessons from Koresh in order to spy on him. On the morning of February 28, the Waco Tribune-Herald had just (coincidentally) published a second inflammatory article on David Koresh in a series entitled "The Sinful Messiah." Rodriguez visited Koresh to assess what effect the negative PR was having, whether the publication Waco Tribune-Herald's publication of Sinful Messiah had incited Koresh and his followers to take up arms or otherwise increase their security measures. The planners were still not sure Koresh had been effectively tipped off.

While Rodriguez was taking his Bible lesson from Koresh, David Jones allegedly returned to the Mt. Carmel Center and gave the news of the impending raid to his father, Perry Jones. Jones interrupted the Bible discussion, called David Koresh out of the room on the pretext that he had a phone call, and told him the news. When Koresh came back into the room, he allegedly told Rodriguez, "They're coming, Robert, the time has come."

We are asked to believe that Rodriguez was "shocked" when he heard the news; he became so agitated, he contemplated jumping out a window to escape before the ATF arrived (Treasury Report, pg. 89). Rodriguez suddenly remembered a breakfast appointment, bolted out of his Bible lesson, jumped in his truck, and drove back to the undercover house. When he got to the undercover house, Rodriguez found the window was raised. A camera was in one of the windows, and it was clearly visible from the outside of the house (doubtlessly within the scope of David Koresh's binoculars.)

When Rodriguez took fast leave of the Mt. Carmel Center he acted like what he was — a man in the know, getting out of the way of a massacre — a man who preferred to be elsewhere when it happened. Just in case everything else failed, the Davidians watched a house guest suddenly remember a "breakfast appointment" in the middle of a Bible lesson and make a mad dash to safety.

The ATF plan was both murderous and suicidal. The evidence indicates that the "bungling" was intended to forewarn the Davidians of the impending attack, to provoke them into defending themselves, and to provide them with easy targets. The ATF agents were led to slaughter to provide the excuse for the first test of the National Response Plan.

It was not Murphy's law. It was a set-up. It was a domestic Gulf of Tonkin incident. And as we shall see later in the chapter, Who Struck John?, it included some powerful backup plans to ensure its success.

Sitting Ducks

The ATF raiders arrived in canvas-topped cattle trailers and parked the trailers broadside to the front windows and door of the Mt. Carmel Center. Had the Davidians opened fire, this maneuver would have provided them with the best target and the highest number of ATF casualties. The Waco Tribune-Herald, March 1, 1993, included a diagram of the position of the cattle trailers. That diagram is confirmed by a Treasury Report aerial photograph (pg. 99), in which the trailers are visible across the front of the Mt. Carmel Center (top of that picture).

This picture of the ambulance and armored personnel carrier (APC) at the Mt. Carmel Center was taken on February 28, 1993, and appeared in The Dallas Morning News the next day, March 1. The caption does not say when the photograph was taken, but the presence of the ambulance and the APC together indicates the APC was on the scene before the emergency vehicle left with its load of casualties.

The ATF troops were ordered to take a position in front of the house with no cover from possible return fire except the thin metal of car bodies that happened to be parked there. If the Davidians had opened fire when the trailers first arrived with the 50-caliber machine gun they were alleged to have, many agents would have died.

But what's going on here? Judging by published news photographs, at least one armored personnel carrier (APC) was on the scene at the same time as the ambulances. Track vehicles are not fast and are not usually driven on paved public roads. As shown in other pictures, these were transported on rubber-tired trailers (e.g., image from Time, May 3, 1993). That this APC was on the scene so soon after the raid implies that it was prepared and transported well in advance in expectation of a firefight. Hence, an innocent American housewife asks, why were the soldiers transported to the Mt. Carmel Center to face a "heavily armed cult" (as it was characterized) with machine guns (as alleged in the warrant the agents were serving) in canvas-top cattle trailers?

There is but one answer: Those government agents were set up like shooting gallery targets, and the raid was designed to provoke a hostile response from the Davidians with high casualties among the agents. Like the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the government strategists were looking for justification to wage war on the Branch Davidians. And as suggested by the evidence in the following exhibits, when Davidians failed to react violently, the military provided its own dead bodies.

Shortly after the text above was published, the Museum received an e-mail from a member of the US military. The e-mail address and other specifics have been removed to protect the source:

"To whom it may concern,"I am very concerned by the evidence your museum puts forward. Frankly, it scares the bejeezus out of me. I am a member of the U.S. Army, and I am familiar with many of the terms in your discussions. I am in the [delete unit] at [delete location].

"… the tactics used in Waco are textbook military. To begin, your assumption that the initial assault was designed to fail is absolutely certain. An objective is NEVER breached during the daytime. The advent of night-vision technology has rendered unnecessary, as the risk is greatly reduced when your opponents are blind and you are not. Also, any planned attack is not conducted without COVER or CONCEALMENT. Also, surprise is key, and security of that element NEVER breached. To understand this, one would have to have an understanding of the overall Military mentality, especially in the combat arms. Loose lips could get you or your buddies killed, so you never mention an upcoming operation.

"Next, the siege. The light and noise were most certainly more than just psychological operations on the Davidians (though that must have been a good testing ground for new equipment). The noise and light probably hid the activities of the actual killings, days before the fire. How could anyone make out the sound of gunshots and explosions amidst all of that chaotic din? Then the clean-up would have to be enacted, and though the Armed Forces are organized, they are anything but quick. It probably took several nights of hard work to cover up the evidence of any wrong doing.

"There were probably more dead in the initial assault … The plan is never to just assault from one side. No doubt there was a rear assault … [text deleted]

"Thank you for the museum,"